Finding Forgiveness in Rwanda

One man’s journey of survival and redemption

“Mommy, where can we run to?”

These heart-wrenching words greet visitors to the children’s exhibit at Kigali Genocide Memorial Center. The child who uttered them before falling victim to one of the bloodiest three months in history is now just a memory enshrined in a black and white photograph, her innocent 7-year-old eyes forever staring out at passersby.

The attempted extermination of an entire people group at the hands of another is an unimaginable history.

“It looked like the devil had taken control of hearts. The spirit of death was hovering over the whole land, even where a husband could kill a wife, where parents would kill children. There was no life.”

But the story of Rwanda does not end with the nearly one million horrific murders that occurred during the genocide of 1994. God is transforming it into a powerful tale of forgiveness, with a young Rwandan named Alex Nsengimana setting an inspirational example for his country and people.

“Nsengimana” means “I pray to God” in Kinyarwanda, and Alex has certainly lived up to the name. In his 25 years, God has guided his steps along a remarkable journey that included miraculous escapes from death during the genocide. It also includes receiving a shoebox gift through Operation Christmas Child—a gift that helped bring him to a strong faith in Jesus and led to the desire to return to Rwanda to plant a church and minister to the people who killed his family.

“I want to be back in Rwanda so I can share the ministry of forgiveness, because that’s the only thing that has continued to heal me,” said Alex, who left his homeland in 2003 to attend school in the United States.

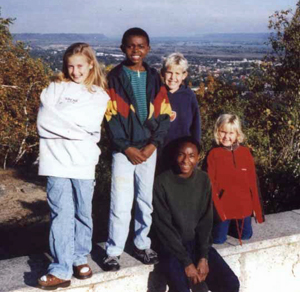

In March, he visited the village where he grew up. Alex delivered shoebox gifts to children unaware of past distinctions between Hutu and Tutsi, and who do not feel the same hatred toward their neighbors as the generations who came before them.

“We are all Rwandans,” said Alex, when asked how Tutsi victims are able to live side-by-side with Hutus who slaughtered their families and friends. “We speak one language.”

Nearly 20 years after the genocide, many Rwandans are able to overlook old tribal, political, and economic divisions that played a large part in the war. But others still face a daily struggle to see murderers walking free. Those who killed husbands, wives, children, and parents may pass victims’ family members at the market, school, even church.

With God’s grace and Christ’s example of forgiveness, Alex believes that his nation can be reconciled. During his visit, Alex reinforced his words with actions by offering forgiveness, in person, to the man who killed his uncle.

When he faced the man who was a neighbor and friend of the one he murdered and uttered words of forgiveness and redemption through Jesus, a burden he had carried for many years lifted from his chest.

But his journey toward peace has not been easy.

Why Me

Even though he was just 5 years old on April 6, 1994, Alex will never forget the morning when the plane carrying Rwanda president Juvenal Habyarimana was shot down.

The president’s death sparked a wave of violence that continued countrywide for three terrible months and claimed nearly a million lives. Among them were Alex’s grandmother and uncle.

Alex never knew his father, and his mother died of AIDS when he was 4. He was left with his older sister and younger brother in the care of their grandmother and two uncles. They lived on a hill in the outskirts of Kigali, in a mud-and-stick house nestled among the coffee trees the family owned and cultivated.

As a young boy, Alex’s job was to fetch water. Like many children, he was easily distracted and often found himself sidetracked, playing soccer with his friends and running through Kigali’s hillside neighborhoods instead of doing his chores. His face broke into a wide grin as he recalled his grandmother spitting on the ground, saying: “If you’re not back by the time this dries, boy you’re going to get it!” Those carefree days ended the moment the genocide started. Nyirabarera, his grandmother, was among the first Tutsi victims to be targeted.

Hutu militia stormed the house one afternoon. Alex, Lillian, and their brother, Fils, watched through the window in horror while their grandmother was tortured and killed.

Several days later a group of men with guns came looking for his uncle, Karara. Alex remembers neighbors and friends among the group that demanded to see Karara’s identity card. After checking the card with its Tutsi ethnic listing, they shot him twice. Because the gunshots did not kill him, the men took a large stick and beat Karara until he died.

“What they did haunted me for many, many years,” Alex said.

Another uncle bribed additional militia groups with beer and food in exchange for the remaining family’s safety, but eventually the resources ran out and Lillian, Alex, and Fils were forced to flee.

“We packed up everything and started walking toward the capital city where my aunt and her family lived,” Alex said.

The three young children often had to hide in the forest or ditches when large buses of Hutu militia rumbled past on the red dirt roads. Eventually, they reached their aunt’s house in Kigali and settled in.

Sleeping through the night was difficult. Alex struggled with nightmares of seeing his family murdered. Bombs rattled the house, often sending shrapnel through the windows, walls, and ceiling.

Still, Alex’s life continued to be spared. One day, a bomb exploded nearby while he was playing marbles with his brother. They quickly huddled together, and a chunk of burning debris flew through the small space between their heads.

“We always wondered how it made it through because the thing was big and hot, but it barely missed our heads,” he said.

Alex began to wonder why he kept escaping death when so many others had not.

“Wherever the Night Would Find Us”

Eventually, the situation became too volatile and the family had to flee.

“Wherever the night would find us, that’s where we would sleep,” Alex said.

For nearly two months they ran, crossing the hills around Kigali. Explosions from bombs and grenades followed them everywhere. At one point, Alex got separated from the rest of his family. Someone opened fire as he frantically searched for them, and bullets whizzed just above his head. One even grazed his hair.

“I always like to say that God has a sense of humor,” he said, laughing. “As I was running, I slipped in something and fell. I had slipped in a cow pie; that’s what God used to save my life. If He can use that cow pie, imagine what else he can use.”

Finally, after what seemed like years of living in terror, the Rwandan Patriotic Front forces drove the Hutu militia out of Kigali. The family returned home, but Alex wasn’t able to enjoy the security for long. His aunt and uncle fell ill, and in the spring of 1995 Alex and Fils were sent to a nearby orphanage.